Improving Training Skill Transfer

Learning professionals realize that training is only effective when participants apply their new skills on the job. With so much focus nowadays on training and retraining the American workforce for the jobs of the future, we are seeing increased attention to this area of evaluation. In my work with companies across America, I have found that skill transfer is the number one training evaluation concern today.

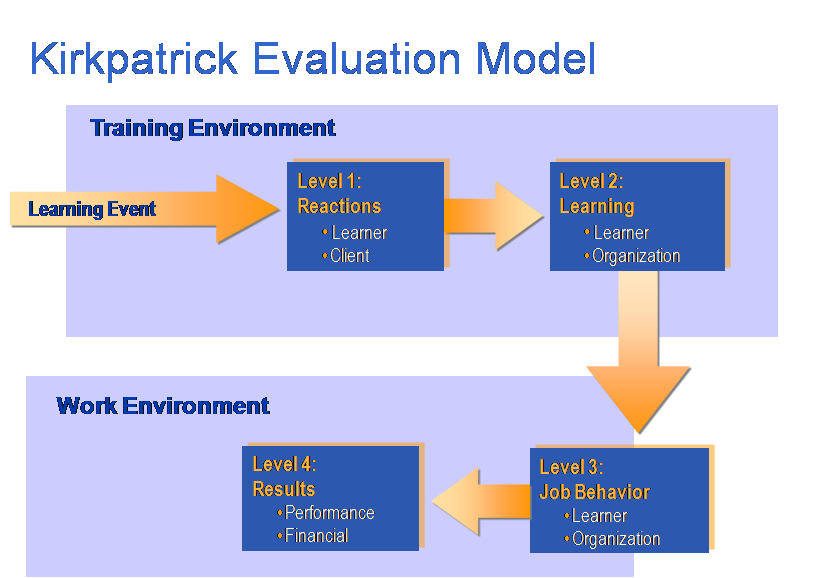

What exactly is “skill transfer?” The concept originated with the seminal work of Donald Kirkpatrick, who called it “behavior change,” the third of the four levels of his evaluation model. To fully understand why level three is such a critical link in training evaluation, consider the contextual model of evaluation, based on Kirkpatrick’s four levels, that appears below.

Level three evaluation occurs at a crucial juncture when learners return to their work environment. If they successfully apply their new skills, their own performance will improve. If individual performance improves for enough workers, the organization’s overall performance should also improve. Performance improvement then leads to better organizational results, measured at level four, in terms of the organization’s financial performance.

Conversely, if skills learned in training are never applied on the job, then the training investment that produced those skills is useless to the organization that paid for it. Even the individual trainees who have acquired new knowledge and skill through formal learning will ultimately not benefit if the skills are untransferred. We know that new knowledge that is never put to use eventually atrophies and disappears into the hidden recesses of our minds. A study of skill transfer conducted in the 1990s by Mary Broad and John Newstrom found that about half of all newly-learned skills are never transferred in a productive way to the workplace. This means that as much as half of the nation’s investment in training is not producing meaningful results. As one of my former bosses used to say, “It’s like shoving money down a shredder.”

Given the importance of boosting skill transfer after training, let us examine the key factors that promote transfer. Researchers have identified four key requirements for successful skill transfer, as listed below:

- Acquiring the necessary skills

- Learners’ desire to change

- Conducive job environment and support

- Rewards for behavior change

Each of these requirements is important and not always easy to accomplish. Taken together, they maximize the transfer of training and the impact of training outcomes in the workplace.

Acquiring Necessary Skills

This factor is so obvious that its implications are often overlooked. Put simply, new skills cannot be transferred if they are irrelevant to the job. To ensure that the right skills are taught to the right people who actually need them, it is imperative to conduct a thorough needs analysis before designing and delivering training. This analysis must include job task analysis to determine the needed job skills and learner analysis to determine the extent and nature of the skills gap.

While most training professionals know this is important, in far too many cases, we are pressured by clients and decision makers to short circuit needs analysis and just get on with delivering the training. This inevitably leads to a poor match between the objectives and content of the training and the needs of the learners and the organization that sponsors and pays for the training. We can certainly learn to perform analysis more efficiently, but we also need to resist the temptation to skip this step altogether and simply accept our clients’ opinions as the truth.

Learners’ Desire to Change

The desire to change is a second key ingredient of skill transfer, since we know that motivation drives behavior. The motivation to change one’s behavior through learning requires two fundamental factors:

- Belief in the need to change

- Exerting effort to change

These two factors are related, since our level of effort in any work is directly correlated with our beliefs about the value and efficacy of that work. If we believe that something is both valuable and possible, we are much more likely to exert the effort required to achieve it.

Trainers cannot directly control learner’s desires, but we can certainly help them see the need to change and can help them calibrate their efforts so that they are working hard and smart enough to affect the desired change. We often reduce this to WIIFM (What’s In It For Me) statements about the value of training. While these are important in instilling learning motivation, they are often insufficient to carry people through the difficulties of learning. I may be convinced that a new skill would be beneficial to me, but if I encounter too much difficulty in learning it, I may become discouraged and give up. Trainers need to candidly reveal the difficulties of their subject matter and design learning events that lessen those difficulties through chunking of content, relevant practice and preparation for application on the job. We also need to do better at meeting the individual learning needs of those we serve rather than adopting one-size-fits-all approaches to training.

Conducive job environment and support

The third factor is one that has received greater attention as organizations struggle to make better use of their training investments. No matter how well we design and deliver new skills, the organization cannot reap the full benefits unless it creates a supportive work environment. Researchers have identified several key factors that create a work environment where skill transfer thrives:

- Supportive supervisor

- Supportive co-workers

- Conducive organizational culture

- Conducive policies and practices

Of these, the supervisor occupies the most important role. Supervisors who take an active interest in the development of their staff and who encourage both the intrinsic desire to change and provide extrinsic rewards for doing so are far more likely to see improved job behavior after training than those who take a passive or indifferent attitude towards employee development.

Supervisors can take a number of concrete actions to improve skill transfer after training, including:

- Model skills and behaviors for employees

- Coach employees to apply new skills

- Provide feedback on how well employees are performing

- Take corrective action when employees fail to apply new skills

- Provide rewards and recognition when employees successfully apply new skills

The second critical factor is supportive co-workers. If one’s co-workers are also actively applying new skills and offering peer coaching to their fellow workers, this can significantly aid and abet the efforts of supervisors. Pairing new employees with experienced ones is a common method for accelerating skill transfer. Formal mentoring and coaching programs are also very important elements of a supportive organizational culture that promotes skill transfer.

Rewards for behavior change

At the end of the day, we all work for the money. Unless learners see tangible rewards for their efforts to learn new skills and boost their job performance, they will not sustain the effort required to change. In today’s difficult economy, few employees can expect a pay raise as a result of training, but employers can do many things to reward employees that don’t cost a whole lot of money.

One area that has drawn increased interest is recognition programs. We all like to be recognized for our good work, and some of us need this more than others. Recognition may come in the form of certificates, awards, public acknowledgment, perks or more desirable work assignments. Many of these things cost little or nothing to provide.

Low cost rewards like gift cards, tickets to entertainment events, paid time off and company-sponsored trips often provide a great return on investment in terms of increased employee engagement, reduced absenteeism and increased productivity.

The next time a client requests training, remember that our job as learning professionals does not end when learners complete their training. Indeed, our job is only half-way finished at that point. The other half is to ensure that the new skills we have worked so hard to instill are actually being put to productive use in support of the organization’s mission and objectives.

Donald J. Ford, Ph.D., C.P.T.

President

Training Education Management LLC

Redondo Beach, CA 90277